Software Renderer in Odin from Scratch, Part X

30th November 2025 • 30 min read

In Part VII](https://marianpekar.com/blog/software-renderer-in-odin-from-scratch-part-vii), we implemented flat shading, a simple technique where we adjust the color of an entire triangle based on the angle between its normal and light direction. Phong shading, named after Bui Tuong Phong, is a little bit more complicated and more computationally expensive since the light is calculated individually for every pixel, as you can see in the following video.

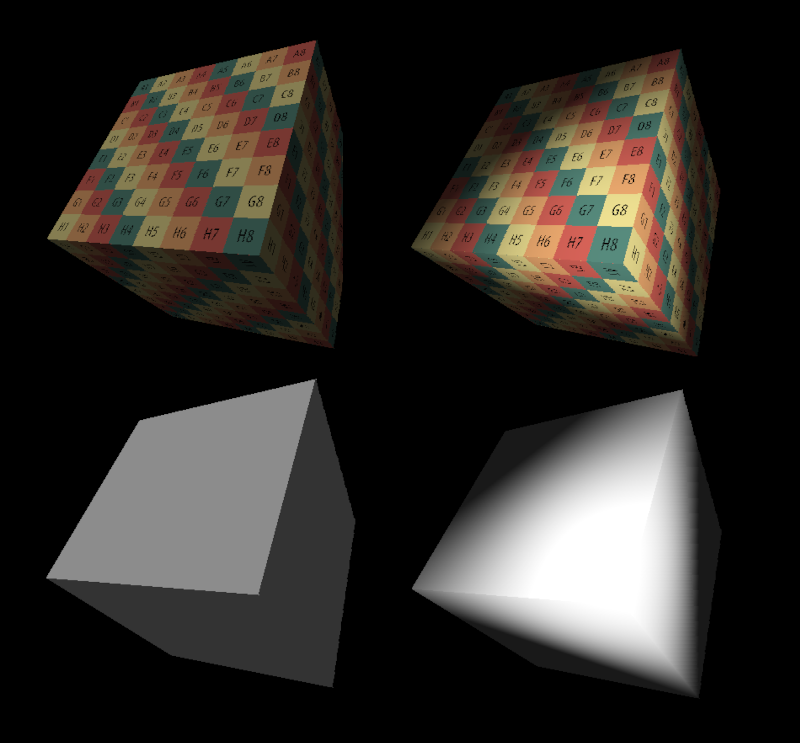

With Phong shading, we calculate the light intensity for each pixel based on the position of the light and the position and normal at each pixel, which we get by interpolating the positions of the vertices and normals across the triangle. The difference is clearly visible when we compare flat shading with Phong shading on a cube.

Updating light.odin

However, before we start implementing new rendering modes, we need to revisit our light.odin file. For flat shading, we only needed a direction, but with Phong shading, we are going to need a point light with an actual position in our 3D space. The point light emits rays from its position in all directions, and in the video below, you can see the difference between flat and Phong shading once again very clearly.

That said, open light.odin and add a Vector3 position to our Light struct as well as to its factory procedure MakeLight.

package main

Light :: struct {

position: Vector3,

direction: Vector3,

strength: f32,

}

MakeLight :: proc(position, direction: Vector3, strength: f32) -> Light {

return {

position,

Vector3Normalize(direction),

strength

}

}

Extending sort.odin

We also need to implement two new sorting procedures. So far, we have implemented one for sorting projected points and another for sorting both projected points and UVs. The second we use exclusively in render modes that involve texture mapping, that's what UVs are about.

In the case of Phong shading, we also need to sort points before projection. In our implementation, we refer to them as vertices or individually as v1, v2, and v3. The new pair of procedures will sort both points and vertices, and one of them will also sort UVs.

Let's open the sort.odin file and extend it as just described. I am not going into details here, since both will be in principle the same as the one we already implemented. We just sorted additional properties of our triangle that we haven't had to sort for the render modes we have implemented up to this point.

SortPointsAndVertices :: proc(

p1, p2, p3: ^Vector3,

v1, v2, v3: ^Vector3,

) {

if p1.y > p2.y {

p1.x, p2.x = p2.x, p1.x

p1.y, p2.y = p2.y, p1.y

p1.z, p2.z = p2.z, p1.z

v1.x, v2.x = v2.x, v1.x

v1.y, v2.y = v2.y, v1.y

v1.z, v2.z = v2.z, v1.z

}

if p2.y > p3.y {

p2.x, p3.x = p3.x, p2.x

p2.y, p3.y = p3.y, p2.y

p2.z, p3.z = p3.z, p2.z

v2.x, v3.x = v3.x, v2.x

v2.y, v3.y = v3.y, v2.y

v2.z, v3.z = v3.z, v2.z

}

if p1.y > p2.y {

p1.x, p2.x = p2.x, p1.x

p1.y, p2.y = p2.y, p1.y

p1.z, p2.z = p2.z, p1.z

v1.x, v2.x = v2.x, v1.x

v1.y, v2.y = v2.y, v1.y

v1.z, v2.z = v2.z, v1.z

}

}

SortPointsUVsAndVertices :: proc(

p1, p2, p3: ^Vector3,

uv1, uv2, uv3: ^Vector2,

v1, v2, v3: ^Vector3,

) {

if p1.y > p2.y {

p1.x, p2.x = p2.x, p1.x

p1.y, p2.y = p2.y, p1.y

p1.z, p2.z = p2.z, p1.z

uv1.x, uv2.x = uv2.x, uv1.x

uv1.y, uv2.y = uv2.y, uv1.y

v1.x, v2.x = v2.x, v1.x

v1.y, v2.y = v2.y, v1.y

v1.z, v2.z = v2.z, v1.z

}

if p2.y > p3.y {

p2.x, p3.x = p3.x, p2.x

p2.y, p3.y = p3.y, p2.y

p2.z, p3.z = p3.z, p2.z

uv2.x, uv3.x = uv3.x, uv2.x

uv2.y, uv3.y = uv3.y, uv2.y

v2.x, v3.x = v3.x, v2.x

v2.y, v3.y = v3.y, v2.y

v2.z, v3.z = v3.z, v2.z

}

if p1.y > p2.y {

p1.x, p2.x = p2.x, p1.x

p1.y, p2.y = p2.y, p1.y

p1.z, p2.z = p2.z, p1.z

uv1.x, uv2.x = uv2.x, uv1.x

uv1.y, uv2.y = uv2.y, uv1.y

v1.x, v2.x = v2.x, v1.x

v1.y, v2.y = v2.y, v1.y

v1.z, v2.z = v2.z, v1.z

}

}

Before we leave the sort.odin file for good, we mustn't forget to extend our Sort procedure group for explicit overloading.

Sort :: proc {

SortPoints,

SortPointsAndUVs,

SortPointsAndVertices,

SortPointsUVsAndVertices

}

Extending draw.odin

In the draw.odin file, we are going to start as usual by implementing a procedure we're later going to call in main.odin. Let's add the one for Phong shading with a solid color first.

DrawPhongShaded :: proc(

vertices: []Vector3,

triangles: []Triangle,

normals: []Vector3,

light: Light,

color: rl.Color,

zBuffer: ^ZBuffer,

projMat: Matrix4x4,

ambient:f32 = 0.1

) {

for &tri in triangles {

v1 := vertices[tri[0]]

v2 := vertices[tri[1]]

v3 := vertices[tri[2]]

n1 := normals[tri[6]]

n2 := normals[tri[7]]

n3 := normals[tri[8]]

if IsBackFace(v1, v2, v3) {

continue

}

p1 := ProjectToScreen(projMat, v1)

p2 := ProjectToScreen(projMat, v2)

p3 := ProjectToScreen(projMat, v3)

if IsFaceOutsideFrustum(p1, p2, p3) {

continue

}

DrawTrianglePhongShaded(

&v1, &v2, &v3,

&p1, &p2, &p3,

&n1, &n2, &n3,

color, light, zBuffer, ambient

)

}

}

This is nothing new for us. We have already implemented several similar procedures, and I know there's a potential to refactor this into more DRY code, code that doesn't repeat the same logic as much. But what we would get by having fewer lines of code, we would pay for in readability, plus it would be easier to break the rendering pipelines we have already implemented and harder to debug individual ones. I think, in this case, the outcome wouldn't justify the price.

Before we move on to implementing DrawTrianglePhongShaded, notice how we pass through the DrawPhongShaded this time also vertices and normals, or to be precise, transformed vertices and transformed normals. We'll get back to this later when we'll be extending main.odin, since we didn't need to transform normals up to this point.

DrawTrianglePhongShaded :: proc(

v1, v2, v3: ^Vector3,

p1, p2, p3: ^Vector3,

n1, n2, n3: ^Vector3,

color: rl.Color,

light: Light,

zBuffer: ^ZBuffer,

ambient:f32 = 0.2

) {

Sort(p1, p2, p3, v1, v2, v3)

FloorXY(p1)

FloorXY(p2)

FloorXY(p3)

// Draw a flat-bottom triangle

if p2.y != p1.y {

invSlope1 := (p2.x - p1.x) / (p2.y - p1.y)

invSlope2 := (p3.x - p1.x) / (p3.y - p1.y)

for y := p1.y; y <= p2.y; y += 1 {

xStart := p1.x + (y - p1.y) * invSlope1

xEnd := p1.x + (y - p1.y) * invSlope2

if xStart > xEnd {

xStart, xEnd = xEnd, xStart

}

for x := xStart; x <= xEnd; x += 1 {

DrawPixelPhongShaded(

x, y,

v1, v2, v3,

n1, n2, n3,

p1, p2, p3,

color, light, zBuffer, ambient

)

}

}

}

// Draw a flat-top triangle

if p3.y != p1.y {

invSlope1 := (p3.x - p2.x) / (p3.y - p2.y)

invSlope2 := (p3.x - p1.x) / (p3.y - p1.y)

for y := p2.y; y <= p3.y; y += 1 {

xStart := p2.x + (y - p2.y) * invSlope1

xEnd := p1.x + (y - p1.y) * invSlope2

if xStart > xEnd {

xStart, xEnd = xEnd, xStart

}

for x := xStart; x <= xEnd; x += 1 {

DrawPixelPhongShaded(

x, y,

v1, v2, v3,

n1, n2, n3,

p1, p2, p3,

color, light, zBuffer, ambient

)

}

}

}

}

Again, nothing really new here. We are calling our Sort with a set of parameters to invoke the SortPointsAndVertices overload, then we floor the X and Y components of our projected points, and after that, we have a flat-top, flat-bottom rasterization algorithm, which we also know well.

As you can see, the DrawTrianglePhongShaded procedure is almost identical to DrawFilledTriangle with just a bit more data that flows through this procedure to DrawPixelPhongShaded, which we call in place where we called a simpler DrawPixel in the case of DrawFilledTriangle, and where we're going to calculate that per-pixel lighting.

Since DrawPixelPhongShaded is the procedure that holds the gist of Phong shading, I am going to go over it a bit more slowly. Let's start with its signature and the parts we are already familiar with from the DrawPixel.

DrawPixelPhongShaded :: proc(

x, y: f32,

v1, v2, v3: ^Vector3,

n1, n2, n3: ^Vector3,

p1, p2, p3: ^Vector3,

color: rl.Color,

light: Light,

zBuffer: ^ZBuffer,

ambient:f32 = 0.2

) {

ix := i32(x)

iy := i32(y)

if IsPointOutsideViewport(ix, iy) {

return

}

p := Vector2{x, y}

weights := BarycentricWeights(p1.xy, p2.xy, p3.xy, p)

alpha := weights.x

beta := weights.y

gamma := weights.z

denom := alpha*p1.z + beta*p2.z + gamma*p3.z

depth := 1.0 / denom

zIndex := SCREEN_WIDTH*iy + ix

if depth <= zBuffer[zIndex] {

So far, we are still on the ground we already know. We skip rendering pixels that are outside the screen, then we calculate barycentric weights and use them for our depth test with the z-buffer to prevent overdrawing.

Now, we're finally getting to the core of Phong shading. For the pixels that made it here, first, we multiply each normal by its corresponding barycentric weight, sum them, and normalize the resulting vector. This is an interpolated normal, a normal for that particular pixel.

interpNormal := Vector3Normalize(n1^ * alpha + n2^ * beta + n3^ * gamma)

Next, we need the interpolated position of the pixel, which we calculate by multiplying each vertex by the Z component of the corresponding projected point and corresponding barycentric weight. We then sum them all together and multiply the result by the current depth.

interpPos := ((v1^*p1.z) * alpha + (v2^*p2.z) * beta + (v3^*p3.z) * gamma) * depth

Do you remember how, in the ProjectToScreen procedure, we stored the inverse W, 1.0 divided by the fourth component of a point in clip space, as the third component of our projected point? Even though at the time it might have looked strange to store projected points as 3D vectors instead of 2D, since we are projecting onto a plane, we need this inverse W again down the pipeline for per-pixel light calculations, just as we needed it for texture mapping. But back to our procedure.

Now that we have our interpolated position, we use it to calculate the direction between the light source and that particular pixel, simply by subtracting the two vectors and normalizing the result.

rayDir := Vector3Normalize(light.position - interpPos)

I named this variable rayDir because we can imagine it as the direction of a single ray of light hitting this particular pixel. The light intensity is proportional to the dot product between the interpolated normal and this ray direction.

intensity := Vector3DotProduct(interpNormal, rayDir) * light.strength

intensity = math.clamp(intensity, ambient, 1.0)

On top of that, we adjust the intensity by the strength of the light, but we also want to clamp it between the ambient and 1.0. We use the lower bound to fake ambient lighting, similarly to how we did for flat shading. With a lower bound of 0.0, pixels too far from the light would be completely black, and since the basic color of our space is black…

The upper bound, as you probably already know, is there because we don't want to exceed the maximum value of each color channel, which is 255, because the rest of the procedure is again nothing new for us. We now just need to multiply the base color by the light intensity we just calculated to get the color to actually draw the pixel on the screen with. Finally, we mustn't forget to update our depth buffer.

shadedColor := rl.Color{

u8(f32(color.r) * intensity),

u8(f32(color.g) * intensity),

u8(f32(color.b) * intensity),

color.a,

}

rl.DrawPixel(ix, iy, shadedColor)

zBuffer[zIndex] = depth

}

}

Before we put this all together, let's quickly implement the last rendering mode in this series, which involves both Phong shading and texture mapping. If you are up for a challenge, you can try it on your own, just look at how we implemented texture mapping for flat shading, and write a new rendering pipeline where you combine logic for texture mapping you already know with what we've just implemented.

Or you can follow along. We start once again by implementing a procedure we will later call from main.odin.

DrawTexturedPhongShaded :: proc(

vertices: []Vector3,

triangles: []Triangle,

uvs: []Vector2,

normals: []Vector3,

light: Light,

texture: Texture,

zBuffer: ^ZBuffer,

projMat: Matrix4x4,

ambient:f32 = 0.2

) {

for &tri in triangles {

v1 := vertices[tri[0]]

v2 := vertices[tri[1]]

v3 := vertices[tri[2]]

uv1 := uvs[tri[3]]

uv2 := uvs[tri[4]]

uv3 := uvs[tri[5]]

n1 := normals[tri[6]]

n2 := normals[tri[7]]

n3 := normals[tri[8]]

if IsBackFace(v1, v2, v3) {

continue

}

p1 := ProjectToScreen(projMat, v1)

p2 := ProjectToScreen(projMat, v2)

p3 := ProjectToScreen(projMat, v3)

if IsFaceOutsideFrustum(p1, p2, p3) {

continue

}

DrawTexturedTrianglePhongShaded(

&v1, &v2, &v3,

&p1, &p2, &p3,

&uv1, &uv2, &uv3,

&n1, &n2, &n3,

texture, light, zBuffer, ambient

)

}

}

Compare this procedure with DrawPhongShaded, and you'll see that the only difference is that now we are also passing through the UV coordinates, and where we previously called DrawTrianglePhongShaded, we now call DrawTexturedTrianglePhongShaded, which we are going to implement next.

DrawTexturedTrianglePhongShaded :: proc(

v1, v2, v3: ^Vector3,

p1, p2, p3: ^Vector3,

uv1, uv2, uv3: ^Vector2,

n1, n2, n3: ^Vector3,

texture: Texture,

light: Light,

zBuffer: ^ZBuffer,

ambient:f32 = 0.2

) {

Sort(p1, p2, p3, uv1, uv2, uv3, v1, v2, v3)

FloorXY(p1)

FloorXY(p2)

FloorXY(p3)

// Draw a flat-bottom triangle

if p2.y != p1.y {

invSlope1 := (p2.x - p1.x) / (p2.y - p1.y)

invSlope2 := (p3.x - p1.x) / (p3.y - p1.y)

for y := p1.y; y <= p2.y; y += 1 {

xStart := p1.x + (y - p1.y) * invSlope1

xEnd := p1.x + (y - p1.y) * invSlope2

if xStart > xEnd {

xStart, xEnd = xEnd, xStart

}

for x := xStart; x <= xEnd; x += 1 {

DrawTexelPhongShaded(

x, y,

v1, v2, v3,

n1, n2, n3,

p1, p2, p3,

uv1, uv2, uv3,

texture, light, zBuffer, ambient

)

}

}

}

// Draw a flat-top triangle

if p3.y != p1.y {

invSlope1 := (p3.x - p2.x) / (p3.y - p2.y)

invSlope2 := (p3.x - p1.x) / (p3.y - p1.y)

for y := p2.y; y <= p3.y; y += 1 {

xStart := p2.x + (y - p2.y) * invSlope1

xEnd := p1.x + (y - p1.y) * invSlope2

if xStart > xEnd {

xStart, xEnd = xEnd, xStart

}

for x := xStart; x <= xEnd; x += 1 {

DrawTexelPhongShaded(

x, y,

v1, v2, v3,

n1, n2, n3,

p1, p2, p3,

uv1, uv2, uv3,

texture, light, zBuffer, ambient

)

}

}

}

}

Again, this is still fundamentally the same thing with the FTFB rasterization algorithm; we are just passing through the UV coordinates to yet another new procedure, DrawTexelPhongShaded.

DrawTexelPhongShaded :: proc(

x, y: f32,

v1, v2, v3: ^Vector3,

n1, n2, n3: ^Vector3,

p1, p2, p3: ^Vector3,

uv1, uv2, uv3: ^Vector2,

texture: Texture,

light: Light,

zBuffer: ^ZBuffer,

ambient:f32 = 0.2

) {

ix := i32(x)

iy := i32(y)

if IsPointOutsideViewport(ix, iy) {

return

}

p := Vector2{x, y}

weights := BarycentricWeights(p1.xy, p2.xy, p3.xy, p)

alpha := weights.x

beta := weights.y

gamma := weights.z

denom := alpha*p1.z + beta*p2.z + gamma*p3.z

depth := 1.0 / denom

zIndex := SCREEN_WIDTH*iy + ix

if depth <= zBuffer[zIndex] {

interpNormal := Vector3Normalize(n1^*alpha + n2^*beta + n3^*gamma)

interpPos := ((v1^*p1.z)*alpha + (v2^*p2.z)*beta + (v3^*p3.z)*gamma) * depth

rayDir := Vector3Normalize(light.position - interpPos)

intensity := Vector3DotProduct(interpNormal, rayDir) * light.strength

intensity = math.clamp(intensity, ambient, 1.0)

// Texture mapping

interpU := ((uv1.x*p1.z)*alpha + (uv2.x*p2.z)*beta + (uv3.x*p3.z)*gamma) * depth

interpV := ((uv1.y*p1.z)*alpha + (uv2.y*p2.z)*beta + (uv3.y*p3.z)*gamma) * depth

texX := i32(interpU * f32(texture.width )) & (texture.width - 1)

texY := i32(interpV * f32(texture.height)) & (texture.height - 1)

tex := texture.pixels[texY*texture.width + texX]

shadedTex := rl.Color{

u8(f32(tex.r) * intensity),

u8(f32(tex.g) * intensity),

u8(f32(tex.b) * intensity),

tex.a,

}

rl.DrawPixel(ix, iy, shadedTex)

zBuffer[zIndex] = depth

}

}

And if you compare this DrawTexelPhongShaded procedure with the DrawPhongShaded, you'll see the only difference is that instead of multiplying the light intensity by a base color, we now multiply it by a texel that we map for that particular point, the same way as we already did in DrawTexelFlatShaded.

For clarity, I included a little comment that says //Texture mapping before that critical part. If you need a refresher, peek into Part VIII of this series, where we discussed texture mapping in more depth.

Extending main.odin

All rendering modes are now implemented, and we just need to incorporate them into our main loop, but first, in main.odin we have to fix the call of the MakeLight factory procedure, since we are now storing both direction for flat shading and position for Phong shading. The first parameter is the position:

light := MakeLight({0.0, 0.0, -3.0}, {0.0, 1.0, 0.0}, 1.0)

Then, as always, we need to increment renderModesCount. We added two new modes, so we are incrementing from 6 to 8.

renderModesCount :: 8

And after we transform our vertices, for rendering modes that involve Phong shading, we also need transformed normals.

ApplyTransformations(&mesh.transformedNormals, mesh.normals, viewMatrix)

Finally, we add calls to DrawPhongShaded and DrawTexturedPhongShaded into our switch over a selected rendering mode. You can sort them as you like, but I like the order when we first have a wireframe mode, then unlit, flat shaded, and Phong shaded with a solid color, and then unlit, flat shaded, and Phong shaded with a texture, so I shuffled the cases a bit, and the result looks like this:

switch renderMode {

case 0: DrawWireframe(mesh.transformedVertices, mesh.triangles, projectionMatrix, rl.GREEN, false)

case 1: DrawWireframe(mesh.transformedVertices, mesh.triangles, projectionMatrix, rl.GREEN, true)

case 2: DrawUnlit(mesh.transformedVertices, mesh.triangles, projectionMatrix, rl.WHITE, zBuffer)

case 3: DrawFlatShaded(mesh.transformedVertices, mesh.triangles, projectionMatrix, light, rl.WHITE, zBuffer)

case 4: DrawPhongShaded(mesh.transformedVertices, mesh.triangles, mesh.transformedNormals, light, rl.WHITE, zBuffer, projectionMatrix)

case 5: DrawTexturedUnlit(mesh.transformedVertices, mesh.triangles, mesh.uvs, texture, zBuffer, projectionMatrix)

case 6: DrawTexturedFlatShaded(mesh.transformedVertices, mesh.triangles, mesh.uvs, light, texture, zBuffer, projectionMatrix)

case 7: DrawTexturedPhongShaded(mesh.transformedVertices, mesh.triangles, mesh.uvs, mesh.transformedNormals, light, texture, zBuffer, projectionMatrix)

}

Conclusion

And that is it for today. During these last ten parts, we have done a lot of work together and learned so much. We learned math concepts like vectors and matrices, we learned about transformations and projections, about UV mapping, rasterization, how to read and parse an OBJ file, how to read inputs, how to calculate lighting for simple flat shading and also for a more complex Phong shading, and several other concepts. But most importantly, we learned how all these things relate to each other. If you followed along through all those ten parts, rewrote all the code, and took care to understand it, you have my huge respect, and you should be proud of yourself.

But wait, the series is not over yet! In the upcoming parts, we're going to cover some optimizations, then we're going to add support for multiple models with different textures, and for multiple lights with different colors that we're going blend in real time, and on top of that, we're also going to implement switching between perspective and orthographic projection. So make sure your project is working as expected, and if not, you can always check this Github repository, where you can find the final states of the project after each part.